War Stories

Over the past few months, we’ve had the opportunity to visit three different countries in which the United States has, one way or another, been involved in a war. Japan, whose horrifying devastation brought a swift end to World War II; Korea, which is divided to this day along geographic, political, and cultural lines; and Vietnam, host to one of the messiest and most controversial wars in our country’s history. The legacy we left behind in each place resonates into the present and beyond, shaping our policies regarding these countries and our own country’s image in their eyes. Understanding the impact our involvement in each region had, and continues to have, is a vital piece of understanding the countries themselves.

In August of 1945, months after the surrender of the Axis forces in Europe, Japanese forces still refused to accept unconditional surrender at the demand of the Allies. The proposed Operation Downfall, a traditional land-based invasion of Japan, promised to be a costly and lengthy endeavor. Rather than risk prolonging the war indefinitely, President Truman ordered two nuclear bombs to be dropped on Japan, targeting the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Over 200,000 people died as a direct result of the bombs, the vast majority of whom were civilians. The Japanese forces surrendered unconditionally days after the bombings, effectively ending World War II.

Today, Hiroshima is a thriving, modern city, most of its scars healed. Some of these scars, such as the famous A-Bomb Dome, have been preserved as monuments of remembrance. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, located roughly at the epicenter of the blast, contains a variety of monuments and dedications to the host of victims. The Peace Memorial Museum, which is extremely well-done, contains photographs and video of the bomb itself; artifacts and remnants such as melted roof tiles, destroyed infrastructure, and torn and burned clothing; and many accounts of both victims and survivors of the bomb. The atmosphere throughout the park is one of sorrow, regret, and an overriding plea to never let this happen again. There was no sense of anger or recrimination, something I almost can’t wrap my head around. To take such a tragic event from your country’s past and use it, not as a political rallying cry or call to anger, but as a demand for peace requires an admirable strength of character and culture.

During World War II, and actually for over 30 years prior, Korea was under harsh Japanese occupation. After annexing Korea in 1910, the Japanese did their best to stamp out any and all Korean resistance, including but not limited to jailing and/or executing political dissidents, protesters, those with higher education, and anyone else considered to be a seditious element. We actually had a chance to visit the largest of these political prisons in Seoul; it felt more like a concentration camp than a proper prison, especially when walking through the “torture implements” displays.

This room was dedicated to photos of a small portion of the people who were executed, starved, or worked to death in the prison

One of the terms of the Japanese surrender in 1945 was that they be stripped of their occupied territories, forcing them to relinquish their 35-year hold on Korea. Hooray! The problem was that at that time, the Soviets controlled the northern reaches of the country, while the Americans controlled the south. Neither side wanting the other’s governmental preferences to control the entire peninsula, the two powers decided to take a page out of Solomon’s book and split it in half. Two US Army colonels, Dean Rusk and Charles Bonesteel (both of which are really cool names), were given about 30 minutes to submit a proposal on where to split the country. Armed with a National Geographic magazine map and presumably after an A-Team style planning montage, they chose the 38th parallel as the dividing line almost completely arbitrarily, and thus North and South Korea were born.

For a few years, this situation was maintained, albeit with some tension as the rulers on both sides of the demarcation considered themselves the rightful ruler of the entire peninsula. In June of 1950, less than five years after the end of WWII and the division of the Korean territory, Kim Il-Sung launched a surprise attack on Seoul with the eventual goal of conquering and reunifying the entire country under his communist government. If there was one thing in the 50’s that the western world, and the US in particular, didn’t like, it was those damn commies, so a UN resolution was adopted calling for worldwide support of the South Korean forces. 21 countries offered their aid, whether by sending in troops, donating money or supplies, or giving medical aid where necessary. Around 90% of the foreign soldiers sent in were Americans.

After a fair bit of back-and-forth, as well as some untimely escalation by China on behalf of North Korea, three years of harsh fighting eventually ended with the border pretty much back where it had started near the 38th parallel. An armistice was signed in July of 1953 which, though ending immediate hostilities, did not actually end the war between the two halves of the country, leaving them technically still at war to this day.

Visiting the UN Memorial Cemetery in Busan, the War Museum in Seoul, and the DMZ border gave a great overview of how (South) Korea perceives the war, the foreign intervention, their northern neighbors, and their next steps forward. The cemetery is dedicated exclusively to the soldiers of the UN member states that sustained casualties in the conflict. There are 2,300 graves, arranged by country, a number of memorials and monuments donated by individual countries, and a flag raising and lowering ceremony each day. One of the centerpieces is a huge monument upon which are carved the names of every foreign service member who died in the war, separated by country and, in the case of the United States’ gargantuan section, by state — similar to the Vietnam memorial in Washington, D.C. The level of respect and gratitude shown to these soldiers at the cemetery is incredibly humbling.

At the daily flag-lowering ceremony, the soldiers salute as the family members of one of the interred pay their respects.

The War Memorial Museum in Seoul is an extremely well-done museum (probably one of my favorites I’ve seen so far) located on the site of the former army headquarters. There are two main sections, one located on the grounds surrounding the main building and the other in the museum building itself. The grounds contain a number of statues and monuments dedicated to the soldiers, both Korean and foreign, as well as to the families that were split apart, either as a result of a family member being killed or by the division of the country itself. The coolest part of the outdoor exhibit, in my opinion, is the hundreds of decommissioned jets, tanks, missiles, humvees, AA guns, and other military paraphernalia either donated or seized (depending on the side I guess) from the US, China, USSR, and Korea’s own military. They even have an entire B-52 bomber on display, dwarfing the rest of the vehicles.

The interior of the museum give a comprehensive chronological account of the Korean War, from the end of World War II through to the signing of the armistice in 1953. There are also a few sections on more ancient warfare in Korea that we unfortunately didn’t get to see due to time constraints. The sections on the war are incredibly detailed, with models, videos, and text in numerous languages supplementing the plethora of artifacts, including uniforms, weapons, and equipment. The displays, once again, spent a great deal of time detailing the contributions and sacrifices of the UN members that became involved in the conflict. We left the museum with a much greater understanding of the causes, specifics, and aftereffects of the war.

The main museum building, with the flags of participatory countries and units arrayed in a circle around the entrance

There are numerous parallels between the Korean War and the Vietnam War, at least in their beginnings. Prior to WWII, Vietnam had been a French colony; after the war, France was granted permission by the Allied forces to reinstate their control of the region. Vietnam, however, had declared its independence at the end of WWII under the leadership of communist activist Ho Chi Minh. This led to a nine-year conflict called the First Indochina War, wherein the Vietnamese overthrew the French and once again declared their independence. There were, at this time, two governments in place — Ho Chi Minh’s communist regime in the north and a purportedly democratic government in the south. A conference was held to develop a solution for the region. This solution, called the Geneva Accords, split Vietnam on the 17th parallel into the communist North and democratic South in 1954, using the Korean armistice of the previous year as inspiration. Rather than ending the conflict, however, the division only deepened it, as both sides considered themselves the rightful rulers of the entire country. By 1960, the United States began sending military advisors to the South, and by 1964 had begun sending troops and air support.

The war was a messy one. Unlike the troop-on-troop fighting in Korea, Vietnam was a guerrilla warfare theater. The Viet Cong conscripted anyone and everyone they could, blurring the line between civilian and soldier, and many villagers took it upon themselves to fight against what they saw as a foreign invasion, laying traps and ambushes in the dense jungle. Many areas of Vietnam are inaccessible even to this day due to thousands of unexploded mines still strewn about the countryside. This style of fighting led the US to employ controversial military tactics such as wide-scale carpet bombings and chemical warfare in the form of Agent Orange, the terrible effects of which persist generations later. By 1973, America had pulled out of Vietnam due to slow progress and dwindling support both at home and worldwide. By 1975, the North Vietnamese had captured Saigon, the democratic headquarters, and the communist regime instated control over the entire newly reunified country.

Both the Korean and Vietnam Wars were begun for similar reasons in countries divided along very similar lines. The difference in outcome has led to very distinct impressions of their respective wars, history of course being written by the victors. These distinctions begin even with the name given to the war; what we call the Vietnam War is called the “War of American Aggression” in Vietnam, which certainly paints a picture of their perspective on the war as a whole. The war is viewed as a reach of American Imperialism, and the official account now teaches that America was intending to install a puppet government in Vietnam, effectively taking control of the country remotely.

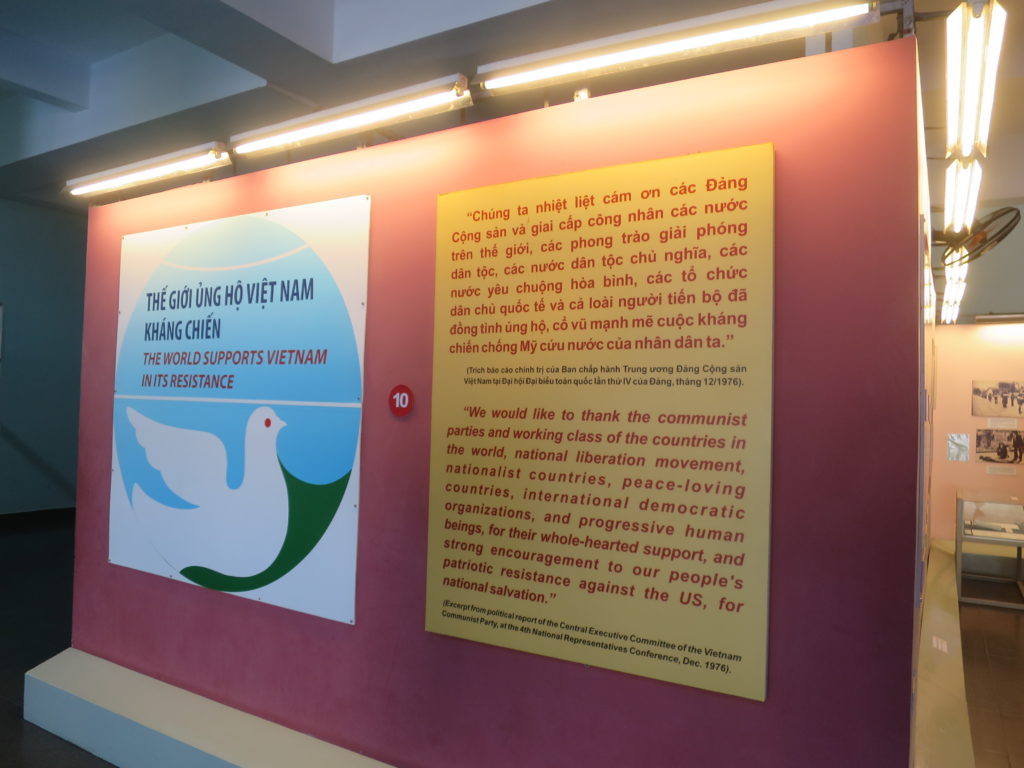

There is a War Museum in Vietnam as well that is very interesting to see, if only for the obvious anti-American slant. The museum gives a very one-sided account of atrocities committed by the South Vietnamese and American forces. In any caption or explanation, the North Vietnamese are referred to as “patriots”, while those in the south are generally called “American sympathizers”. There was a whole room dedicated to different activist groups around the world protesting American involvement in Vietnam, trying to show how the whole world stood with them against the American Imperialists. One thing I found particularly interesting was how the word “propaganda” doesn’t seem to have the same negative connotation it does in the west. They proudly displayed propaganda material from the war era, and labeled it exactly that.

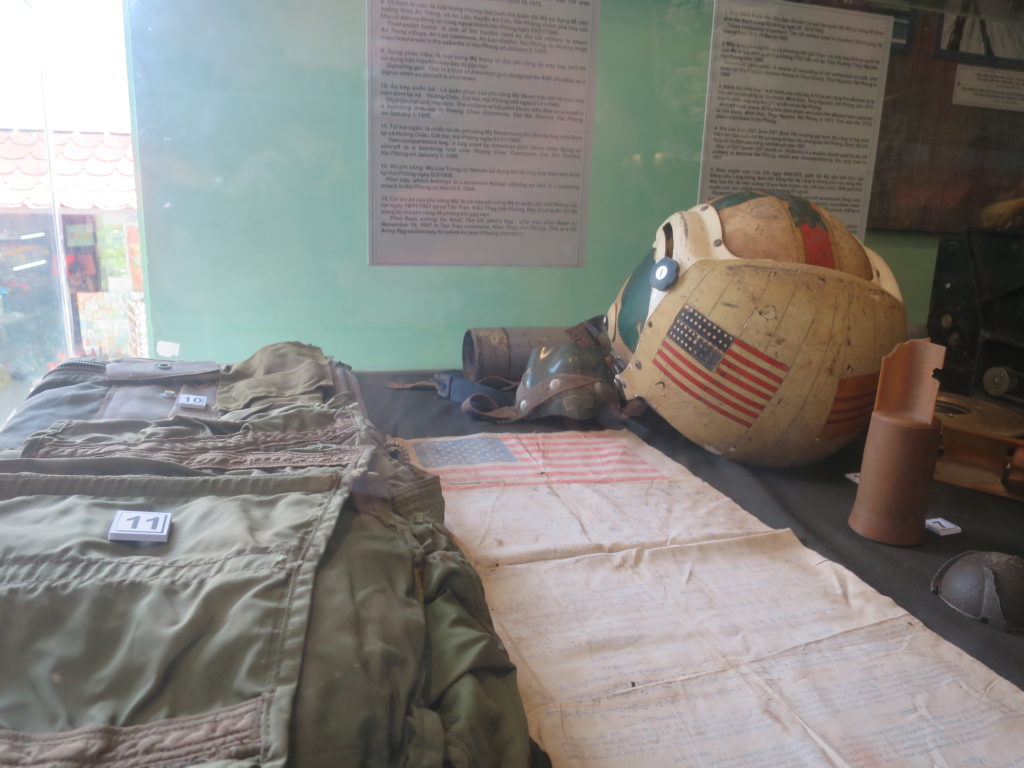

The uniform of a downed American pilot, displayed somewhat less reverently than the display from the Korean museum

It’s interesting how the whims of history can so change a country’s trajectory. How differently would World War II have ended without the advent of nuclear warfare? What might Korea look like today had reunification occurred at the end of the war, either under the control of the democratic south or the totalitarian north? Had Vietnam remained divided along geographic and political lines, how different might those two halves be today? Without American involvement, these three conflicts would have undoubtedly followed entirely different trajectories. Learning from the events and their long-term effects on the countries involved gives an important perspective on the impact, both positive and negative, that our involvement can have, and should serve as reminders of how those effects can affect entire countries’ paths.